20.29 Writing

Table of contents

- Structure and Contents

- Style

- Citations and reference sections

- Conceptual illustrations and plots

- Proofreaders

- Resources

General guidelines

- Revise often

- Ask colleagues for friendly reviews

- Spell-check

- Avoid plagiarism

Structure and Contents

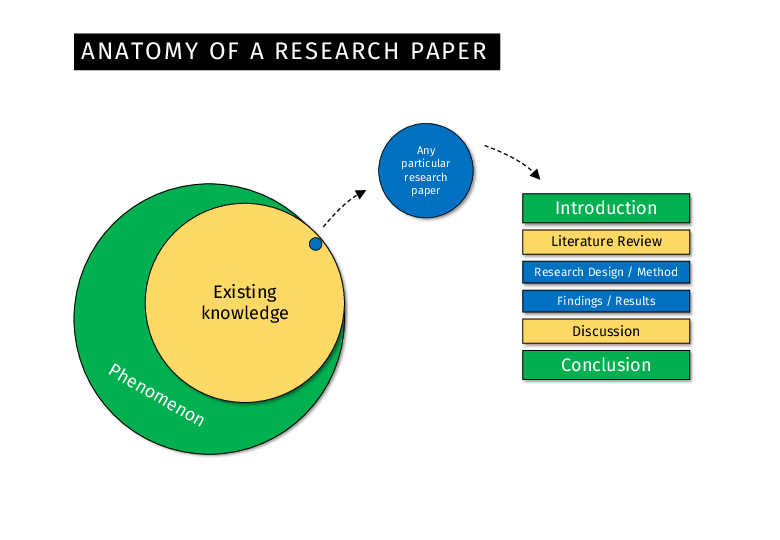

The default structure outlined below may need to be adapted to the thesis or paper at hand. Each section has its own scope, as illustrated in the figure below. It is recommended to use active voice (“I” or “We”) instead of passive voice (commonly used in German).

Abstract

The abstract acts as a point-of-entry for the reader, providing a first overview of the research study, namely, the motivation for the study, the methodological approach taken and a summary of the main results. In addition, the purpose of the research study should be clearly defined. Typically, an abstract consists of around 200 words.

Introduction

The introduction should precisely outline the purpose of the study as well as the research question that is sought to be answered. By briefly outlining the context of the study in terms of content and time, the reader acquires a quick overview. A key aspect of the introduction is the presentation of the motivation for conducting the study. This gives the reader a basic understanding of the topic and underpins the relevance and importance of the study. The relevance as well as the purpose can further be highlighted by using an appropriate quotation.

The building blocks of Lange an Pfarrer (2017) may be helpful:

- Common Ground: Establishing common ground involves presenting the current state of the literature and ensuring that the reader is in agreement with the basic assumptions, boundary conditions, and key concepts. This step is crucial for gaining the reader’s interest and tacit consent, making them more receptive to the forthcoming arguments and discussions.

- Complication: After establishing common ground, introduce a complication that challenges the current understanding or highlights a gap in the literature. This complication could be a problem, puzzle, or twist that makes the reader realize the inadequacy or incompleteness of the existing academic conversation.

- Concern: To make the complication compelling, explain why it matters. This involves demonstrating the significance of the gap or issue identified. The concern step is about showing the practical and theoretical implications of the complication, emphasizing why it is essential to address this gap in the literature.

- Course of Action: Describe the approach or methodology that will be used to address the identified complication. This could involve developing new constructs, modeling relationships, exploring processes, or synthesizing existing theories. The course of action should be clearly explained, logically structured, and directly aimed at resolving the complication.

- Contribution: Finally, articulate how the research will contribute to the academic conversation. This entails explaining the novelty and significance of the findings and how they advance understanding in the field. The contribution should also suggest future theoretical exploration and practical implications for management and organizations.

The final paragraph of the introduction gives an outline of the structure of the study, that is, the approaches taken in each step of conducting the research study are briefly described. This gives the reader a clear picture of the composition of the study, i.e., what can and what cannot be expected of the study.

Background

This section (could also be named Literature Review or Conceptual Framework) sets the theoretical and conceptual context of the study and grounds the leading assumptions in theories. This is done by outlining and citing pertinent work. Here, the author can present the acquired background knowledge that is relevant for the following sections of the study. This background knowledge also helps in building the conceptual framework of the study.

The literature review should focus on concepts as opposed to authors and historical development (cf. Webster and Watson, 2002). It is also possible to use a conceptual framework to structure the literature synthesis. Provide precise definitions of those concepts that are central to your work, emphasize concepts rather than authors, and do not include your own judgment in the background section. Use established definitions and concepts and provide a justification when adapting them.

A graphical representation of the framework helps to illustrate complex theoretical constructs as well as the boundaries of the research study. The explicit statement of the conceptual framework not just informs the reader, it also guides the author in conducting the research.

Relevant background literature can be found in journals such as those listed in

- the AIS Senior Scholars’ Basket of Journals

- the VHB Jourqual Ranking

- or conferences such as ICIS and ECIS.

Papers can be accessed through the Bamberger Katalog, a search on Researchgate, a search on Google, or by contacting the authors.

Guidelines on searching the literature are provided by Webster and Watson (2002).

Methodology

The methodology section describes a systematic and goal-oriented approach to answer the research question. Hence, the selection of the research method needs to be consistent with the research questions. The approach may be, for example, empirical, analytical, comparative, systematic, historic, or hermeneutic (Goethe Universität). The methodological approach needs to be described in detail; appropriate reporting standards for the research method should be considered (such as PRISMA for literature reviews); it should be possible to understand the methodological procedures based on the thesis. For example, it is necessary to provide the formulas of regression models.

Results

In this section, the author presents the results of the study. In case they are presented by means of figures and/or tables, the results should be clearly legible. Furthermore, in the case of figures, it is recommended to use vector graphics as this ensures good readability without the need to pre-specify the font size within the figures. An example figure and table can be found in the template contained in this repository.

Discussion

In this section, the author provides a discussion of the results and is thus able to draw an informed conclusion. More precisely, the discussion is an evaluative summary of the research study in relation to the research question. In general, the discussion can be divided in three parts. First, the results should be tied to the research question, thus presenting the reader a solution or improvement to the identified problem space. Here, for example, the author can draw on empirical findings introduced in the Results section to support his or her argument. Next, the author should outline the limitations of the research study by critically examining the used research approach. Limitations might comprise, for example, a limited time frame considered in the research study, or the individual refinement of a specific research method due to time constraints. Finally, suggestions for future research avenues should be provided. These suggestions may be in line with the limitations, as this allows other researchers to build on the present work by extending or analyzing it. In summary, the Discussion section presents the results in relation to the research question as well as restrictions of the study and suggestions for future research in the respective domain.

Conclusion

The conclusion contains a summary of the research study. In contrast to the Discussion section, in which the main results are presented, here the key contributions of the work are showcased. A well-crafted conclusion answers the research question stated in the Introduction. By so doing, the author clarifies to what extent the research study has presented a solution or improvement to the examined problem space.

Declarations

This section may contain an “Availability of data, materials, and code” statement (e.g., linking to a GitHub repository or a digital appendix), and acknowledgements.

Style

The style guide of Strunk & White (1999) summarizes many instructive recommendations.

Writing concisely

Write as concisely as possible, avoiding general statements, such as:

- “There is a research gap.” - State what the gap is specifically and why it is important to address it.

- “Current knowledge is insufficient.” - State for what purpose current knowledge is insufficient.

Tense

Present Tense

- Use for general truths, facts, and accepted knowledge

(e.g., “Water boils at 100°C”). - Describe what the paper does or contains

(e.g., “This study investigates…” or “The results indicate…”). - Refer to figures, tables, or conclusions in the paper

(e.g., “Figure 1 shows…”).

Past Tense

- Describe specific methods or experiments conducted

(e.g., “We analyzed the data using SPSS”). - Report specific results or findings from the study

(e.g., “The analysis revealed a significant correlation”). - Refer to prior research

(e.g., “Smith et al. (2020) found…”).

Topic sentences

To write in a clear manner, it is helpful to focus on topic sentences (first sentence of each paragraph, which gives a clear outline of what is covered in the paragraph). Good examples of topic sentences can be found in top-tier journal papers like the one of Davis (1989):

Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Ease of Use

What causes people to acceptor reject information technology? Among the many variables that may influence system use, previous research suggests two determinants that are especially important. First, people tend to use or not use an application to the extent they believe it will help them perform their job better. We refer to this first variable as perceived usefulness. Second, even if potential users believe that a given application is useful, they may, at the same time, believe that the systems is too hard to use and that the performance benefits of usage are outweighed by the effort of using the application. That is, in addition to usefulness, usage is theorized to be influenced by perceived ease of use.

Perceived usefulness is defined here as “the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would enhance his or her job performance.” This follows from the definition of the word useful: “capable of being used advantageously.” Within an organizational context, people are generally reinforced for good performance by raises, promotions, bonuses, and other rewards (Pfeffer, 1982; Schein,1980; Vroom,1964). A system high in perceived usefulness, in turn, is one for which a user believes in the existence of a positive use-performance relationship.

Perceived ease of use, in contrast, refers to “the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would be free of effort.” This follows from the definition of “ease”: “freedom from difficulty or great effort.” Effort is a finite resource that a person may allocate to the various activities for which he or she is responsible (Radner and Rothschild, 1975). All else being equal, we claim, an application perceived to be easier to use than another is more likely to be accepted by users.

Concept-centric style

Especially in related work sections, it can be tempting to summarize one study after another. This author-centric style can be hard to read because it often fails to explain how the concepts and findings of studies are related. A concept-centric style can be more effective to organize prior research

Example of an author-centric style

Author A (2001) has studied the acceptance of group support systems and found positive effects on group performance. Author B (2002) has studied expert systems at IBM and found mixed effects on organizational performance. Author C (2003) has surveyed executives and documented diverging views on the benefits of decision support systems.

Example of a concept-centric style

Prior research has examined the effect of decision support systems on various outcomes. There are multiple studies reporting consistent and positive effects on organizational performance (Author A 2001, Author B 2002). In contrast, effects on individual performance were mixed. Studies that measured performance objectively tended to report positive effects (Author C 2020, Author D 2021), while studies of perceived performance did not report significant effects (Author E 2005, Author D 2006).

Webster and Watson (2001) provide advice on constructing a concept matrix.

Citations and reference sections

Citing allows us to make the results of others understandable and give proper recognition to the authors. There are two main reasons why we cite: firstly, to respect copyrighted works, and secondly, to adhere to the principles of good scientific practice by appropriately acknowledging the contributions of others.

In information systems or computer science, indirect citation is usually used, as it is more about the theories, studies and results and not about the direct wording.

The following examples use Markdown syntax. For docx formats, please use a reference manager plugin (such as Zotero).

Your reference manager should support the standardized citation styles of csl.

In-text citations

In-text citations can be parenthetical or narrative (see APA style).

- Example parenthetical citation:

Fitness trackers were found to have mixed effects on sedentary behavior (Smith et al. 2006). - Example narrative citation:

Smith et al. (2006) analyzed the effectiveness of fitness trackers.

Word-for-word quotations (parenthetical or narrative) must be identified by quotation marks and a page number must be given:

- Example word-for-word quotation:

For fitness trackers, "a substantial degree of inaccuracy in measuring sleep quality" was found (Smith et al. 2006, p.111):

Parenthetical citations tend to be preferred over narrative citations because they put more emphasis on the content, concepts, or findings instead of the authors.

In markdown, parenthetical in-text citations are created based on the [@author2000;@author2010] syntax while narrative in-text citations are created based on the @author2000 syntax (link). The unique IDs (e.g., author2000) are used to link citations to the corresponding elements in the BibTeX file.

In the Reference Bib

References should be as complete as possible, including the relevant fields. Each reference should be listed once (not multiple times). Examples with relevant fields are summarized below.

Checklist for BibTeX files

ENTRYTYPEset correctly (e.g., “article” or “inproceedings”)authorformatted correctly (Wagner, G. and Prester, J.)titlecomplete and in lower casejournalfield complete and in title casevolume,number,pages,doifields added

- Journal articles

@article{LeeAnderson2001,

doi = {10.1006/COGP.2000.0747},

author = {Anderson, John R},

journal = {Cognitive Psychology},

title = {Does learning a complex task},

year = {2001},

volume = {42},

number = {3},

pages = {267--316},

}

- Conference Papers

@inproceedings{LeeAnderson2001,

author = {Weber, Matthias and Remus, Ulrich and Pregenzer, Michael},

booktitle = {Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems},

title = {A New Era of Control: Understanding Algorithmic Control in the Gig Economy},

year = {2022},

}

- Books:

@book{Kolb2014,

author = {Kolb, David A},

title = {Experiential learning},

year = {2014},

publisher = {FT press},

}

- Essays in collected editions:

@incollection{Anderson1984a,

author = {Anderson, Richard C},

booktitle = {Theoretical models},

title = {Role of the reader's schema in comprehension, learning, and memory},

year = {2018},

pages = {136--145},

publisher = {Routledge},

}

- Websites

@online{Microsoft2018,

author = {Microsoft News Center},

title = {Microsoft to acquire GitHub for $7.5 billion},

year = {2018},

url = {https://news.microsoft.com/2018/06/04/microsoft-to-acquire-github-for-7-5-billion/},

}

For URLs, use the complete WWW address including the transmission protocol (usually “http://”) in lower case (unless upper case is mandatory for the retrieval).

- To cite software, datasets and other artifacts, CiteAs is useful.

Program that can be used for citation is “Zotero”. You can find the program and how to install it here.

Conceptual illustrations and plots

For conceptual illustrations, PowerPoint is currently recommended.

- Ensure alignment etc.

- For PDF submissions, extract it as PDF (vector graphic with embedded text).

- For Word submissions, extract it as EMF (vector graphic with embedded text).

To plot findings, the R package ggplot2 is recommended. Ggplot2 is a powerful library and allows us to automatically update the figures when the findings change.

It is possible to edit ggplot2 plots with LLMs (e.g., ChatGPT).

Proofreaders

Upwork:

- Zaryyab Nayab Mughal

- Mary Graybeal

Resources

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319-340. doi:10.2307/249008

Lange, D., & Pfarrer, M. D. (2017). Editors’ comments: Sense and structure—The core building blocks of an AMR article. Academy of Management Review, 42(3), 407-416. link

Strunk, W. & White, E. B. (1999). The elements of style. Link

Webster, J., & Watson, R. T. (2002). Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: Writing a literature review. MIS Quarterly, 26(2), xiii-xxiii.