30.07 Pedagogy

This page summarizes pedagogical resources and evidence-based teaching strategies.

Table of contents

- Main Pedagogical Framework

- Evidence-based practice

- Syllabus Design

- Rules and Classroom Management

- Formative feedback

- General student feedback

- Projects and Publications

- Resources

Main Pedagogical Framework

Gestaltung von Hochschullehre, Action Design Patterns

Curriculum development according to Thomas et al. (2022):

- Step 1 Problem Identification and General Needs Assessment

- Step 2 Needs Assessment for Targeted Learners

- Step 3 Goals and Objectives

- Step 4 Educational Strategies

- Step 5 Implementation

- Step 6 Evaluation and Feedback

Rahmenempfehlungen WI

Evidence-based practice

Hattie (2009) aggregates evidence from over 800 meta-analyses on learning and teaching, offering a substantive knowledge base to guide our teaching efforts (PDF).

TODO : a summary will follow

Syllabus Design

- Basic information (Instructor, contact and availability, dates, degree, prerequisites, format online/in person, state whether/when attendance is mandatory)

- Course description with teaching philosophy (link to pedagogical foundations, include safety and inclusiveness statement)

- Goal and learning objectives

- Course outline: contents in a timeline

- Assessment (Grading) and student responsibilities (possibly a “how to succeed” section)

- Materials (access) and resources

Examples:

- NYU/JS

- NYU/Data science

- NYU/Java

- UCF/Systems software

- Hertie School of Governance Introduction to Collaborative Social Science Data Analysis

- Bamberg/PSI

Rules and Classroom Management

Rules affect student behavior and teaching conditions. Strict rules can have several advantages, such as (1) setting clear expectations, (2) reducing free-riding, or (3) allowing instructors to be more supportive instead of disciplining students. For example:

- In the open-source project, the rule is that students only participate if they contribute actual code to the group project. Students know that they are expected to contribute code before a predefined deadline and that the contributions will be checked. Given that students are not assigned to a group and do not receive a grade without contributing code, free-riding (having the others work without putting in much effort) is limited. In addition, students may take proactive ownership of their work, and ask instructors and teaching assistants for help. This allows us to play a more supportive role, instead of trying to discipline students towards the end of the project.

Formative feedback

It is essential to collect formative feedback (“how well students are able to understand/follow the contents during the course”) and adapt accordingly (see Hattie 2009).

We collect feedback using (embedded) Rustpads for anonymous open questions, and Google Forms for structured (anonymous) feedback. Another option is Pingo.

These tools are preferred to paid solutions like Mentimeter or Tweedback.

General student feedback

- Create opportunities for students to meet and form study groups

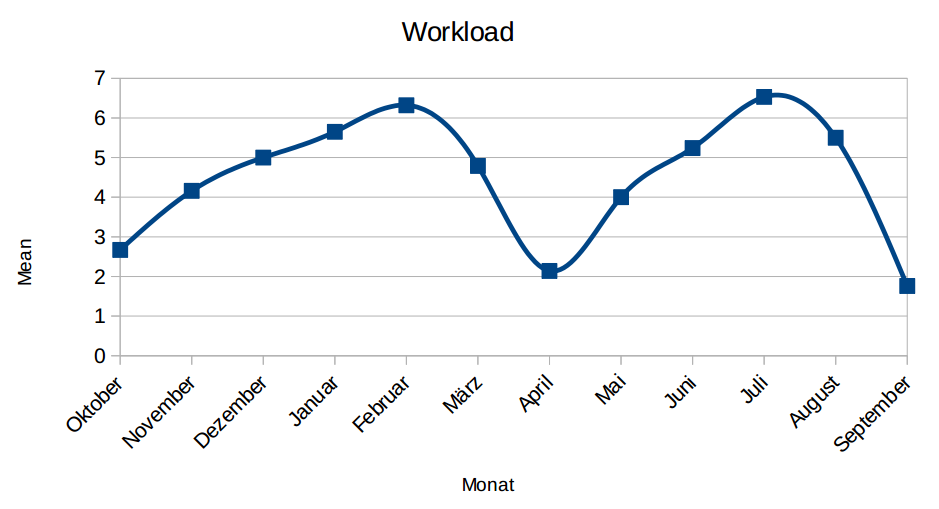

- Consider student workload

Projects and Publications

Resources

Journals/Materials

- Journal of Information Systems Education

- ACM SIG CSE - Computer Science Education

- CAIS - IS pedagogy and teaching case section

- Journal of Information Technology Teaching Cases

See 37-literature.

Courses

Books

Bain, K. (2004). What the best college teachers do. Harvard University Press.

Keller, M. M., Hoy, A. W., Goetz, T., & Frenzel, A. C. (2016). Teacher enthusiasm: Reviewing and redefining a complex construct. Educational Psychology Review, 28, 743-769.

Thomas, P. A., Kern, D. E., Hughes, M. T., Tackett, S. A., & Chen, B. Y. (Eds.). (2022). Curriculum development for medical education: a six-step approach. JHU press.

Hattie, J. (2008). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge. (library)